– Wadeisor Rukato

The second half of 2017 has been a particularly dynamic time when it comes to African elections and the transfer of power amongst political elites. Just over two weeks ago, on the 21st of November, Robert Mugabe submitted his resignation ending his 37-year presidency. Few Zimbabweans could have imagined this would happen in their lifetimes. The 10th of October election in Liberia was disputed after one of the running parties filed a complaint with the National Electoral Commission (NEC) and requested a rerun of the elections. In August alone, both Kenya and Rwanda took to the polls. Kenya has only recently concluded this process with the re-election of Uhuru Kenyatta after the original August 8 election results were challenged. President Kenyatta’s inauguration took place on Tuesday the 28th of November.

For the youth in Rwanda, the August 2018 election marked the first time that the post-genocide generation voted in a National election. This fact went largely unnoticed, however, amid strong international criticism of President Paul Kagame’s landslide victory and his so-called ‘well-disguised, iron-fisted, typical African strongman leadership’. Young Africans took to social media to respond to criticism against the outcomes of the Rwandan election, arguing that “… the Rwanda story is a success story” for Africa, despite its imperfections. Given the impressive post-genocide turn-around in the country, this is not an easily disputable claim.

In Kenya at least 80% of the country’s population is aged 35 and below. Before the August 8 Election, analysts speculated about the potential of the youth vote to swing the election as the campaigns of presidential candidates floated on promises of the reduction of unemployment and the creation of opportunities for the youth. In Rwanda, where over 50% of the population is considered youth, young people were encouraged to participate actively in the country’s election and pre-election activities.

I spoke to young people from Kenya and Rwanda to find out their thoughts about the elections in their countries.

Rwanda

“The Rwandan model is ‘different’. After the genocide against the Tutsi, it was a foregone conclusion that Rwanda will be a failed state” wrote Isaac Rugamba who disapproved strongly of international criticism against President Paul Kagame’s electoral victory and the 2015 constitutional referendum that allowed him to run for an additional term. Having been in Rwanda both during the referendum and during the election, Isaac described the mood in his country as “jubilant and celebratory”, marking a time during which the people of Rwanda took stock of the Rwanda Patriotic Front’s (RPF) achievements.

Isaac voted in the in the 2017 Rwandan election as a first-time voter. “The unique privilege of voting and choosing our leaders is something our forefathers fought and paid the ultimate sacrifice for”. When asked whether he felt empowered by his ability to vote, he said yes, specifically because of decentralisation in the country. Decentralisation in Rwanda is a reform that, since 2000, has transferred previously centralised power and resources to the local levels in the country.

According to Isaac, because of decentralisation Rwandans have the ” ability to hold leaders to account at every level and vote non-performing leaders out of office” and because of this, they are empowered. As mentioned earlier in this article, young Rwandans played an important role in this years election and were encouraged to exercise their right to vote. The youth particularly supported and helped facilitate the pre-election campaigns; “the volunteers, speakers, medics etc. were mostly young people”. President Kagame went as far as acknowledging the youth in his acceptance speech, commending their contribution to the smooth running of the pre-election campaigns.

Internal optimism about the state of politics in Rwanda is not always externally reinforced. The state of human rights issues in the country forms the basis of recurring criticism against Paul Kagame’s leadership. This is to the extent that Rwanda has sometimes been highlighted as one among other global cases in which economic growth and reform are celebrated to the neglect of human rights issues and the shortcomings of a tightly controlled state. The story of Diane Shima Rwigara, a strong Kagame critic, is a case in point. Rwigara had hoped to stand as a candidate in the August 4 election but was barred from doing so after the electoral commission claimed that she had failed to submit enough “supporters’ signatures and [that] some of the names she did send in belonged to dead people”. Rwigara was later arrested on charges of forgery and tax evasion. The silencing of opposition and critics certainly doesn’t contribute points to Rwanda’s democracy scorecard.

Kenya

“Currently there is a fetishization (if I may call it that) of one’s right to vote. Kenyans view voting as a duty rather than a right”. Disillusionment about elections, scepticism about the value of one’s vote and a lack of faith in the standing candidates underpinned Mutala Musau’s decision not to vote in the August 8 Kenyan election. Mutala had little faith in Uhuru Kenyatta, Raila Odinga or any of the other candidates that ran in the election. While some would criticize him for failing to exercise his democratic right by participating in the election, he believes that a worthy leader ought to be demanded by the people before they relinquish the power held in their vote by electing a sub-par candidate. “I will not sell my vote for money, for false promises, for ethnic affiliation, to root out the current leadership only to replace it with a leadership that might be less damaging,” Mutala said, elaborating on why, as a young Kenyan, he does not feel empowered by his ability to vote. For him, an opportunity to choose the slightly better candidate, “the lesser of two evils”, was not reason enough to cast a vote on the 8th of August 2017. For many young Africans, who feel disempowered and disillusioned about the currency of their votes, the ‘to vote or not to vote’ question is easily answered; they simply do not vote.

Harriet Kariuki, who was in China at the time of the election said that, although she would have wanted to, she was unable to vote because China is not yet part of the diaspora vote for Kenya. To be sure, there are currently only 5 countries from which Kenyans in the diaspora can vote; Burundi, Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda and South Africa. For the remainder of the three million plus Kenyans living outside fo the country- sometimes referred to as the 48th county- this is undoubtedly a sore point.

As the Kenyan election unfolded there were issues that came to the fore as having the potential to define the outcomes of the elections. Perhaps most notable among these was the tribal divide in Kenya, especially given the ethnic-based violence that left more than 1000 people dead during the 2007-2008 post-election period. “In truth, there is really only one source of tension in this, and indeed every Kenyan election since 2007, and that is Tribe- most Kenyans will not be happy with this answer…” said Lionel Oduol, commenting on the primary tensions of this year’s election. Harriet agreed on this point, adding that voters tend to ignore strong manifestos, rather focusing on the ethnicity of a particular candidate.

Other defining factors of this year’s election include corruption and the scepticism about the actual independence of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC). With an electronic feature added to the vote counting process in this year’s election, controversy arose after there was a delay in the publishing of the 34A forms which caused a subsequent discrepancy in the verification of the electronic vote count. Delays in the release of official result data caused a delay in the verification of the results which put the credibility of the election results into question. Therefore, in addition to considerations about who showed up to vote and in what numbers, this year’s Kenyan election forced us to reconsider the role, responsibility and power of those who count the votes in determining the outcome of an election.

For many young people, this election was marked by a considerable amount of online and offline dialogue on the critical issues that defined it. According to Harriet, there was “…a great conversation happening [during the election period] on educated tribalism where young people [tried] to understand how they can look and think past their own tribe”. There were also members of the youth who vied for political seats, Boniface Mwangi being prominent among them. Mwangi was unsuccessful in his campaign for the Starehe constituency in Nairobi.

While Lionel agrees that Kenyan youth were active in this year’s election, he is critical about how honestly they engage “in candid discussions around the issues facing the country, and why they have chosen to vote the way they did”. As a challenge to this status quo, he committed to engaging in uncomfortable conversations with people who don’t share the same political views as him in a bid to drive the discourse on elections among the youth away from ethnicity and toward “issues that are actually affecting the country”.

Food for thought

Given a history in African countries of strong men presidents who disregard electoral processes and indiscriminately lengthen presidential terms, the constitutional referendum in Rwanda raised interesting questions about the relationship between presidential terms, the ‘will of the people vs. the constitution’ and the acceptable brands of democracy for African countries. An additional issue to consider in the Rwandan case is succession and the responsibility that leaders who have ruled for long periods of time have in terms of sufficiently grooming someone to take over, or better yet, allowing sufficient political participation for capable individuals to run for office. The Zimbabwean case rings loud on the succession issue.

Unemployment continues to be a factor that limits the ability of young people to make a living in Kenya, Rwanda and across the continent. This breeds disillusionment and frustration, especially when elected officials fail to translate the shiny job-creation strategies in their manifestos into tangible opportunities for the youth. When elections are a performance rather than a mechanism for holding leadership accountable, and if ‘to vote or not to vote’ is the question, many young people will simply not vote.

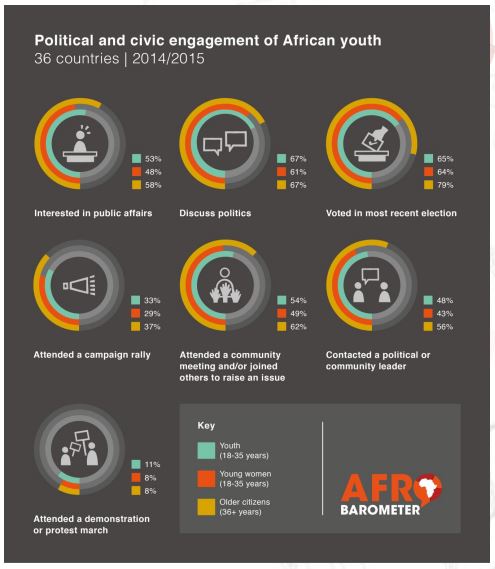

According to a 2016 Afrobarometer study, “political and civic participation amongst African youth is declining and is particularly weak among African women”. African youth (aged 18-35) report lower rates of political participation than their elders across a variety of indicators including voting in national elections. Measures of interest in and discussion of politics differs across the 36 countries that the study covers. It is found that interest levels increase with ” age, education, and material security”. Youth who are fully employed are the most likely to show an interest in public affairs. In terms of electoral participation, specifically voting, it is found that electoral participation decreases with education levels.

This being the case, how are African leaders addressing issues of empowerment and political and civic engagement amongst the youth? At a continental level, the African Union (AU) has shown awareness of the development opportunities that the youth bulge in Africa presents and declared that 2017 would be themed the “year of investment in youth to harness the African demographic dividend”. The roadmap for the thematic year sets out the immediate actions for focused and expanded investments in Africa’s young men and women. According to former AU Chairperson, Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, ” key investments in the youth of Africa today are critical to Agenda 2063 and to elevating Africa to be a strong and influential global player”. Youth empowerment policies have also been initiated at regional and national levels with guidance from the African Youth Charter (AYC), which is a “political and legal document that serves as the strategic framework that gives direction for youth empowerment and development at continental, regional and national levels”.

In terms of access to media among the youth, Afrobarometers survey shows that the most frequently used source for accessing news and information among African youth is still via the radio. Social media does, however, remain an important tool for information sharing and organising during election periods. While local and international media can tend toward a focus on the grand and sometimes conflicting narratives (#kenyaburning vs #peacefulkenya), in both Kenya and Rwanda it was on Twitter and Facebook that young people began to have meaningful, uncensored conversations about the elections.

Commenting on coverage of the Kenyan election Harriet had the following to say; “international media [showed] a burning Kenya and local media [showcased] an extremely peaceful Kenya with no protests. This explains why I only use the mainstream media as a secondary with my primary source being social media”. An additional factor to consider regarding access to the internet and online communication by the youth during elections is the capacity of the state to crack down on these activities and block access to the internet. In recent times, countries including Ghana, Ethiopia, Congo and Uganda have either restricted or completely blocked access to the internet during elections. Governments are increasingly realising the power of social media to assist in information sharing and coordination both among the youth and the voting population in general.

In 2018 Zimbabwe, Sierra Leon and Cameroon are among the African countries that will conduct general elections. With Africa consistently highlighted as having the youngest population of any continent in the world, it will be imperative to observe how youth in these countries engage with, talk about and shape the election processes in their countries.